All Washed Up : on 21 Grams

21 Grams is written in a tidal mode wherein fragments of future events wash up in the present before the crash of the wave. These non-linear elements are never flashbacks, but always anticipate what is to come; nor are they associated with the consciousness of any of the characters, but rather the omniscience of God, or Fate itself. The effect of this is to confront the viewer with a mosaic of clues, which must be penetrated before the story can be mentally constructed, so creating a delay in the exposition. Eventually, however, to reach home, the narrative must pass the structural markers with which we are familiar. In 21 Grams the inciting incident is clearly the accident which radically affects the lives of all the main characters; the 1st turning-point comes when Paul, played by Sean Penn, makes the decision to investigate the identity of the donor of the heart he has just received; the mid-point crisis comes when he is given, not only the identity of the driver responsible for the death of his heart’s donor, but, also, a gun; the 2nd turning-point comes when he, apparently, carries out his intention and shoots the driver, Jack, played by Benicio del Toro — but this is a false resolution.Despite the continuous penetration of the narrative present by tidal waves from the future, we now discover that our perceptions have been manipulated in just such a calculated a way as in a genre picture, such as The Sixth Sense. The final act now progresses in a more straight forward fashion. Previously, Paul had appeared to be motivated in a quite magical way; he received another man’s heart and took on his feelings, both for his wife, and for revenge on the perpetrator of his death, as if they had come with the flesh. In the only misjudged and unconvincing scene of the whole film, we now discover that, contrary to her previously stated position, Christina, played by Naomi Watts, is the true motivator of the revenge killing. An audience revelation shows that Paul did not shoot Jack, but shot into the ground and told him to disappear, and, in a final twist Jack turns up at the motel demanding to be shot. What follows, with Christina battering Jack with a lamp and Paul shooting himself, is marked as the climax by the only expressionistic device in the film, a dipping of effects and a loud buzz on the soundtrack. The plot is comprised of a knot of three strands, that of Paul, Jack, and Christina, (with the more up-beat throughlines of Paul’s wife and Jack’s wife braided in counterpoint), and each of these strands has a pivot-point. With Paul it comes when he leaves his home in the middle of the night to go to Christina; with Jack it is when he unsuccessfully attempts to hang himself; with Christina it is when she accepts the drugs offered by a friend. In order for the film to become a whole, however, these strands must be unified in the structure. Only one specific act can serve a structural function and drive the narrative forward. 21 Grams begins, before the main title, with a shot of Paul brooding while Christina sleeps, and this clearly sites him as the lead character. Despite the exceedingly baggy and defocused exposition, which follows, he remains the centre of concern because he is the only one in a dramatic situation which urgently demands resolution.

So, it is Paul’s decisions, which drives the action forward through the second act, but then something strange happens. In the third act, Paul suddenly becomes, what every theorist warns against, a passive protagonist. First, it is Christina’s venom, that fuels the drive, which Paul ineffectually attempts to carry out; then it is Jack’s over-whelming guilt which triggers the climax, enacted by Christina in a rage, while Paul lies on the sofa. His passivity is further emphasised in the epilogue where he lies dying on a hospital bed, while his thoughts are spoken in the film’s only voice-over.

Because of the tidal nature of the narrative, events are stretched over a far greater duration of the film than normal. However, if we take the point when an action is completed or made explicit as the time index we can get an approximate chart of the structure. Interestingly, the mid-point (often the strongest structural marker) is almost exactly halfway through the duration of the film. The first act at over 45 minutes is extremely long, as one would expect, because it is containing much of the material that would normally occur later in the structure. The 2nd turning-point occurs just short of two-thirds of the way through, which results in a fairly symmetrical form but one quite different from the Hollywood paradigm. It is clear why the first act is (over) long, but what is the significance of the excessively short second act? In the accepted paradigm (established by Syd Field in the late 70’s), the middle act is twice the length of both first and third acts. This is because it is here that the development takes place, the character arc is enacted, and change takes place, either deep within the main character, or in the means he uses to effect change in the story world. But in 21 Grams there is no fundamental change — and this is a key point of the theme. As Paul’s wife, played by Charlotte Gainsbourg, says, “I thought after you had a new heart you’d change.” To which Paul shrugs, and says, “So neither of us changed.” Similarly, Jack thinks that he can change by making his life over to religion, but as his wife, played by Melissa Leo, remarks, “Inside you’re still the same old Jack.” Neither men, nor Christina through the use of drugs, can escape the wretchedness of their predicament. The whole of the second act is therefore akin to a fantasy of self-delusion.

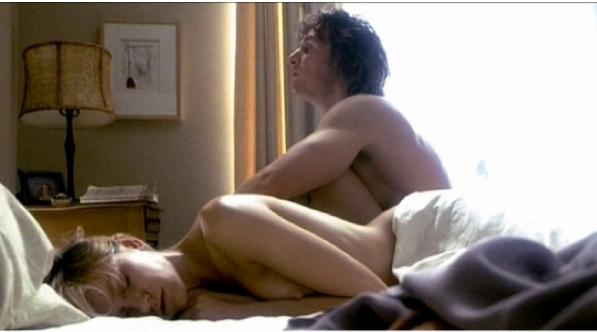

Every form carries with it an ideological implication. It was a triumph of the Hollywood movie, as it evolved, to find a form that minimized the set-up in order to move as fast as possible into the action. This was a neat expression of an ethos, which later became typified, in the advertising slogan, Just Do It! It put faith in the ability to get on with things, sort out problems along the way, and give whatever it took to get things done. 21 Grams, however, has arisen from an almost diametrically opposed culture and point-of view. The opening shot of 21 Grams, (and the only shot of the whole film which is repeated), of Paul sitting on the bed, in moody post-coital contemplation, sets the frame for the whole film. The writer/director, Arriaga and Iñárritu, are not so much interested in action as contemplation and acceptance, not so much in change as surrender. They take on the pose of a frightened child who is afraid to build up her hopes too high less the pain of disappointment should prove too much to bear. From the start, this film is not at all like the heroic tales of Homer. Whereas there “jeopardy stolen from the climax” is used to energize exposition with glimpses of the excitement to come, and so build suspense to a glorious climax, the non-linear approach of 21 Grams works in a quite opposite direction. Here, images of the distress and degradation awaiting are used to undercut any heroic pretensions, or delusions of self-improvement. Every hopeful move is immediately followed by the bitter irony of its outcome, every positive image by one of bleak degradation. There is no escape from the wretchedness of the human condition; it is the exposition of this fatalistic theme that is the raison d’être of the long first act, the truncated second act, and indeed, the whole film. Whereas the Hollywood idea of rising action might be said to diagram a male erection, the trajectory of 21 Grams is more like a flaccid droop. It does not ascend any mountains, but rather flops into a stagnant pool that gurgles and bubbles but goes nowhere. Roger Tucker

[This article was written in response to an exchange with Linda Aronson on “stealing jeopardy” as a means to overcome the extended set-up. It is cited as a dissenting view in her book, The 21st Century Screenplay: a Comprehensive guide to Writing Tomorrows Films, (Allen & Unwin, 2010).] |

|