The Joker & the Thief: on ADAPTATION by Charlie and Donald Kauffman

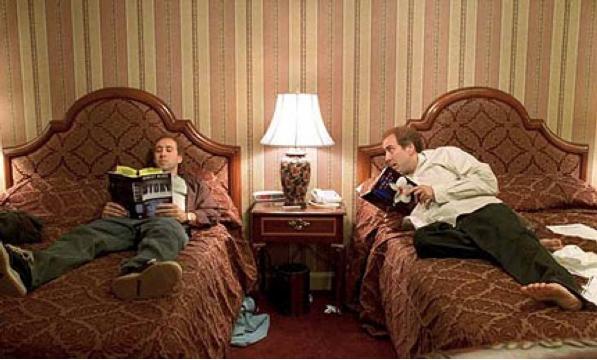

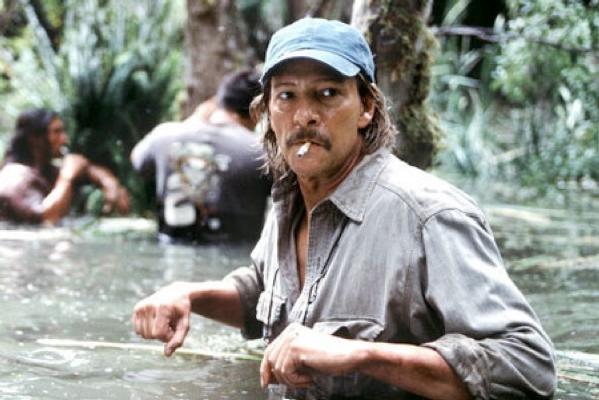

Adaptation is a zany protest against formula scriptwriting. But is it truly an artist's heart-felt cry of anguish, or just a half-baked cake served up for the Indy market? Charlie and his twin brother, Donald appear not only on the credits as joint writers, but also as characters in the film, both played by Nicholas Cage. But wait — Charlie Kaufman is not fat and balding as portrayed in the film, and he has no brother Donald. Our writer has ingenuously split himself down the middle into two faux naïve characters, or opposed comic perspectives. On the one hand we have Charlie, whom, the trailer tells us, “lives the way he writes — with great difficulty”. On the other, Donald, who “writes the way he lives — with foolish abandon”. By giving the former character his own name, the writer signals his identification, and, by the same token, disowns his slick alter-ego, Donald. So, while Charlie ponders the seemingly impossible, of writing a film about flowers, Donald lashes together a bunch of clichés and comes up with a killer script which Charlie’s agent loves. The problem which incites the drama is Charlie’s assignment to adapt for the screen a prize-winning non-fiction book, The Orchid Thief, by Susan Orleans, (played by Meryl Streep). But, immediately, he runs slap, bang, into writer’s block. The very things he loves about the book, snare the adaptation. On screen, Charlie protests that the book has no story, but, in fact, almost from the beginning, the screenplay piggy-backs on the narrative of the book, for its forward momentum.

The book, at the same time, is used as a metaphoric, or Special World to Charlie’s and Donald’s Ordinary World of Hollywood. In this Susan mirrors Charlie in finding life difficult to live, while the title character of the book, John Laroche, (charismatically played by Chris Cooper), like Donald, lives life with foolish abandon. At the centre of it all the "Ghost Orchid" represents the elusive beauty and passion which they all seek. By way of this twin narrative, the script can be broken down further into four main throughlines — (The Focus Story), Action: John / Donald, Passion: Susan / Amelia; (The Contextual Story), Conscience: Charlie / Susan, Power: The Hollywood System / The Law. And, interwoven through these, is a complex Meta-throughline, meditating on life and its representation, with characters as diverse as Darwin and Robert McKee. Surprisingly, this screenplay about a screenplay gives form to a film that rocks — until, that is, it comes to the end of the book’s narrative. This is structurally only the mid-point of the film, but, to talk in these terms is already to fall into just the kind of formulaic thinking that Charlie is desperate to avoid. The book ends without resolution, desire unfulfilled, in a metaphor of our eternal yearning. So why is it that the real Charlie Kauffman, just as the character with the same name, feels compelled to go on, where the book does not? While the surface of Adaptation is positively zinging with attitude, the form into which this material is melded is eerily familiar — and Charlie Kauffman is as familiar with it as anyone. His namesake on screen protests that writing is a journey into the unknown — “it’s not building one of your model aeroplanes.” But, the old plans still seem stuck in the real writer’s head. The on-screen Charlie has, by now, listed, just about, every device by which Hollywood makes fabulous our humdrum experience — including, what is often hoisted as its saving grace, “characters learning profound life lessons.” From this point on, the real Charlie Kaufman will progressively commit every sin. Without the motor-power of Susan’s narrative, Charlie is forced to venture out, beyond the page, into real life. He goes to New York to meet the author of the book, but fails to connect. Instead, following the advice of brother Donald, he sneaks into a seminar by, script guru, Robert McKee, who reinforces Charlie’s agony by telling him to “Wow them in the end”, because the end makes the movie. McKee’s traditional aesthetic is summed up by a later aside, that Casablanca is the greatest screenplay ever written. But the undoubted power of Casablanca’s ending derives from an appeal to consensual values, which are nowhere so apparent today. Faced with this, Charlie gives up the ghost, and calls in his alter-ego, Donald. It is of note that Donald’s instant hit screenplay, The 3, has multiple personality disorder as its subject. This would appear to be the real screenwriter’s problem, (or cherished symptom), too. On screen, the brothers sing Happy Together, but, what’s really going on here seems better summed up by the words of a celebrated Bob Dylan song — “There must be some way out of here, said the Joker to the Thief”

From now on sensitive Charlie tags along behind slick Donald, and the characters of the adapted story are violently travestied. We have lashings of sex and violence, orchids, in effect, are turned into poppies, and the whole thing is brought to an end by — McKee’s ultimate sin — a deux ex machina, in the shape of a crocodile. But, worse is yet to come: after a smaltzy death scene of Donald, we are asked to believe that Charlie learns a “profound life lesson”. By having fat, balding, Charlie, within the film, set up all the screen writing tricks which can then be assigned to brother Donald, the third member of The 3, the real Charlie Kauffman, strikes a cool pose, of post-modern irony. This is the purpose of all the crazy montagages of the meta-throughline, which come to rest on a simple shot of flowers, going through their diurnal routine, while Hollywood traffic speeds past in the background. Wow! That’s kool, man! Mock McKee and then use him! It seems that Charlie Kauffman has eaten his cake and has it, too. But, is it Charlie, or is it Donald? And who’s kidding who? Roger Tucker |

|